OCULUS MUNDI

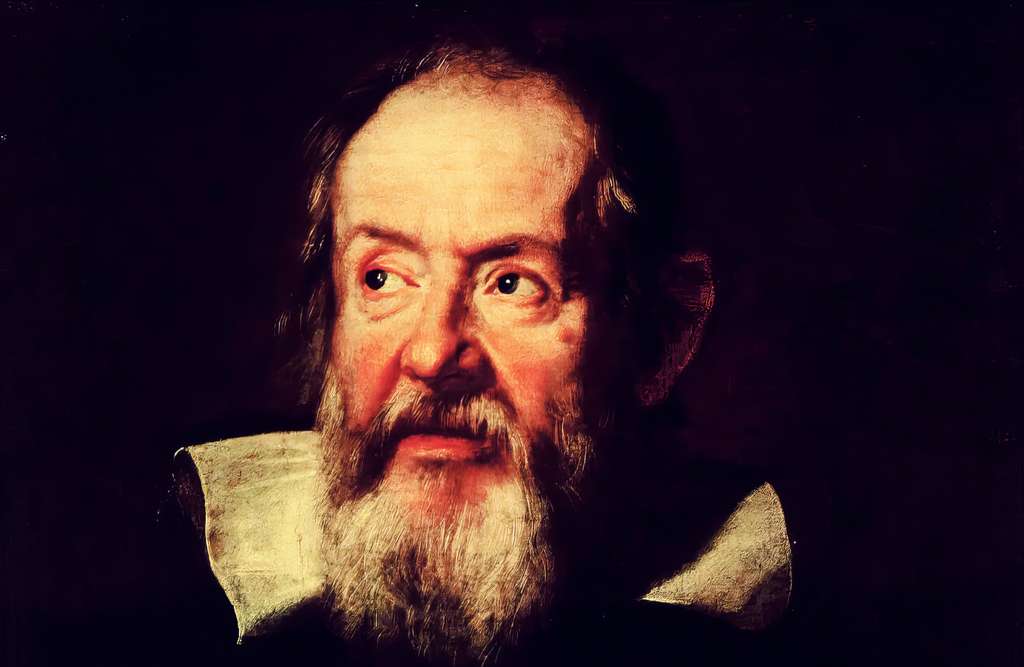

Galileo Galilei: gaze on the Universe

This is the latest multimedia project by Andrea Centazzo. It follows The Seer, dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci, and Imaginary Travel, inspired by Marco Polo. As in those works, this project is structured as a reflection on vision and experience—here focused on Galileo Galilei, whose gaze transformed the understanding of the world through observation. Sound, image, and spoken text are used not to narrate a biography, but to explore the act of seeing as a form of knowledge.

Galileo Galilei stands at the threshold of modern thought, a figure whose life and work mark the transition from received belief to empirical witnessing. In an age when the heavens were sealed in tradition, Galileo’s gaze opened them. He did not merely look upward; he refracted the very act of seeing itself. This show, Oculus Mundi, is a meditation on that emergence: the movement from darkness to light, from silence to articulation, from astonishment to understanding.

Like the celestial bodies he observed, Galileo’s story unfolds through phases. We begin in the quiet province of his youth, where questions stir beneath conventional certainties. Here, in those early moments of curiosity, lies the seed of all inquiry: the restless insistence that what is unseen might yet be true. It is not a dramatization of biography, but a contemplative excavation of the internal rhythm of discovery.

The telescope—Galileo’s instrument and his metaphor—becomes the axis of transformation. With it, the Moon ceases to be a perfect sphere ordained by doctrine and becomes a world with mountains and valleys; the stars multiply beyond counting; Jupiter’s companions dance in orbits unimagined. What was distant becomes immediate, what was fixed dissolves into motion. The show uses this shift not as spectacle alone, but as a lens for our own encounter with evidence, ambiguity, and wonder.

Yet the narrative does not shy away from the tension inherent in seeing what others cannot, or will not, accept. Galileo’s conflict with the authorities of his time—the struggle between conviction and coercion—is presented not as polemic but as an inquiry into the cost of truth. The trial, the censure, and the silence that followed are refracted through language, light, and sound to evoke the subtle interplay between restraint and resistance.

Finally, Oculus Mundi looks beyond Galileo’s own horizon to the legacy he inaugurated. The cosmos he revealed was not a final map, but an invitation—a vast field of questions that extend from his earliest sketches to the instruments of today. In this concluding movement, the show renders the heavens not as a distant spectacle, but as the enduring locus of human imagination.

This multimedia presentation is disciplined in its simplicity. Visuals unfold with clarity; music and sounds are measured and deliberate; sound emerges from silence with precision. Every element serves the central inquiry: what does it mean to see? And having seen, what does it mean to speak what one has seen?

Oculus Mundi is not simply about Galileo Galilei. It is about the act of looking, and through that act, the act of becoming aware—of worlds, of truths, of the relentless human reach toward light.